This chapter contains two sections:

Humanization, Art, and Writing in the ELA Classroom

Multimodal Brainstorming with Word Clouds

Humanization, Art, and Writing in the ELA Classroom

by Ameila Inderjeit

For the 170+ versions of my heart, in year one of teaching.

Introduction

On April 23, 2020 The New York Times published an article analyzing the influence of creators, during the COVID19 pandemic. Josh Zimmerman, a life coach and creative advisor shared his reflection of the time, stating “Creators don’t separate from their work because they are their work.” Though societal norms often associate creators to the arts, the unsung heroes creating everyday inspiration are teachers. Teachers are creators. Creators of lessons, assignments, exams, activities, and most importantly, 170 students, per year. As creators, we do not separate from our work. Our students come to mind all hours of the day, our lessons, the activities we succeed in, fail in–creating a classroom that brings out the best in our students, is neverending. However, to serve our students, we must recognize the errors in our teaching, and constantly strive to improve our practice. A portion of this improvement includes teaching to undo colonization in the classroom, otherwise known as decolonization.

Tuck and Yang within “Decolonization is not a metaphor” define decolonization as the act of bringing “…about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life…” (Tuck and Yang 1) adding that the term “…is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools” (Tuck and Yang 1). The complication in addressing the repatriation of Indigenous land and life, specifically the Lenape native inhabitants of New York, include the extensive history and exposition colonization in our country carries. For educators to make strides in undoing colonization in the classroom, we must take the initiative to understand and approach decolonization education, at its basic form. Nikki Sanchez, an Indigenous media maker, environmental educator, and PhD candidate on Indeigenous Governance advocates that the steps towards decolonization are capable for all to enforce, defining its initial steps as “learn[ing] who you are and where you [come] from, [while] address[ing] the oppressive systems and histories that enable you to occupy the territory you now do.” (Sanchez 10:51). Educators hold the power to begin the process of decolonization in the classroom, not only through teaching students of the oppressive systems currently in place, but recognizing these oppressive systems and their roots in our curriculum.

The proposed practice on decolonization, within this chapter, emphasizes the role of humanization in the ELA classroom, through the use of art and writing. The goals of this are not meant to contribute to current indigenous erasure. Rather, the practice aims towards the efforts needed to be taken by educators, to encourage students to identify who they are, where they come from, and cultivate an understanding towards the oppressive systems and history that are intertwined within their lives, today. Repatriation to Indigenous land and life cannot occur unless we, as educators, make the effort and take pedagogical steps towards contributing to the decolonization of our classrooms.

Paulo Freire’s humanizing pedagogy will be utilized to establish the framework for “humanization,” as used in this chapter. Friere defines humanization as, “…the process of becoming more fully human as social, historical, thinking, communicating, transformative, creative persons who participate in and with the world (Freire, 1972, 1984).” (Salazar 126). Analyzing this definition through the perspective of educators, advocates that humanization in the classroom will focus on empowering students to achieve a greater level of “fullness” to participate as informed, empathetic members of society.

It is worthwhile to note, Freire explains, “Humanization cannot be imposed on or imparted to the oppressed; but rather, it can only occur by engaging the oppressed in their liberation.” (Salazar 126). This chapter will build on activities and pedagogical practice intended to liberate students through art and writing within the English Language Arts, ELA, classroom. Educators “Imposing,” or forcing humanization into their lessons, or onto students, will not succeed in building classroom empathy, making strides towards decolonization. As Zimmerman notes, “Creators don’t separate from their work because they are their work.” Educators who wish to incorporate humanization in their teaching must strive everyday to do so. Their work is endless, and will often go unrecognized, however the impact such practice will hold over students, ultimately promotes their liberation.

Activities

Creating activities embedding writing and art into humanization, require creative thinking, patience, and, above all, trial and error. Creating relationships with students is the first step in encouraging empathy within classrooms. There is no unified way to create relationships with students, nor will you be able create bonds with all of your students. Sometimes you may connect with a majority, other times, not a single one. Nevertheless, it is the effort you make, to connect, that students will remember. It is worth noting, that it is never too late to connect with your students. While you may be presented with difficulties trying to connect to your students mid-year, after they have an idea of who you are, if you truly wish to know your students, each holds a story waiting to be told.

A successful introductory activity in my classroom, includes student intake surveys. These surveys include questions that range from favorite movies, music, and books, to whether students have computer/internet access at home. I attempt to get creative with the surveys, having the questions being displayed in different fonts and positions on the page, printing them on colored paper. Doing this encourages the “fun” students feel, and furthers the idea that you wish to get to know them, rather than them robotically filling out an in-take form for the year. Furthermore, I tell students “answer to your best ability,” a majority of the time, students complete the entire form, while others skip questions they are uncomfortable answering–and this is okay. The goal within these surveys is to have students share what they are comfortable with. Students will often take time to open up, however as an educator, you must take the initiative to welcome this environment.

While conducting these surveys, it is important to recognize two steps you must make to introduce empathy and humanization into your classroom. First, students need modelling to understand the task at hand. If you would like your students to open up and be vulnerable with you, you must set a model in doing so. To do this, I have students engage in an activity called “Get to Know Ms. Inderjeit,” prior to completing the survey. The activity features 25 true or false statements about me. Students are tasked to determine whether a statement is true or false. While the process of students completing the activity is daunting, as you have 34 students staring at you to decide whether or not you did take ballet for seven years, it is important to note that the emotions you encounter are the same they experience, answering questions about their own life. Going over this activity is a fun way for students to get an idea of how conversations will work in class, while setting the stage towards a classroom that emphasizes and recognizes personal identity. While you are the teacher, students will also recognize you are a person outside of the classroom, something they often overlook.

The second step towards successfully encouraging humanization in your classroom, includes reading student surveys for comprehension, not completion. This task is immensely difficult, and while I am nowhere near being a master educator, here are a few tips I have picked up amongst my first year. Reading the work students produce is more important than their test scores and transcripts. The work students produce will always reveal something about who they are. It is up to you to take these surveys and make note of who your students are. My initial notes pay attention to students who do not have internet access, or have specific requests in regards to the parent/guardian they prefer teachers to contact. This allows me to determine the parameters of my assignments, while taking student living conditions into account. From there, I try to make notes on their surveys of things I can relate too. Some examples include commenting on favorite movies, “Avengers End Game,” books, 1984, Animal Farm, and music, i.e. I like this artist as well! When you are able to comment, and recall student interests, they remember, and recognize your efforts. This doesn’t happen overnight, and if I am honest, I rushed to return my surveys, rather than reading them to the extent I could have. However, through my in-class references of the “favorites” I did remember, the look of happiness students share for a brief moment, is worth the effort and time–a piece of advice I will be taking as I continue to teach.

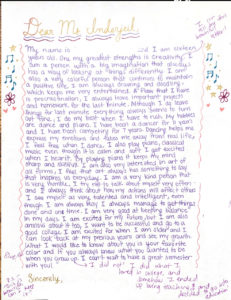

This leads me into the second humanization and arts activity ELA teachers can benefit from, “Introductory/Check-in” arts Assignments. These assignments can happen routinely, randomly, as a do-now, homework assignment, exit ticket, etc., however I do advise they be used at least once during the start of your semester. The purpose of this assignment is to have students share their response to five pivotal questions, while engaging in an art form of their choice. Students are tasked to select one of the following: Snapchat, poetry, photographs, a playlist, TikTok video, letter, artwork and introduce yourself themselves. Their mini-introduction” must address their: (1) greatest strength, (2) character flaws, and (3) hobbies/interests. Additionally, students must answer the following: (1) who are you? (2) how do you see yourself? and (3) what are you excited for? What are you anxious or fearful for? The questions are cultivated for you to get to know your students, as this assignment is done at home, for them to be honest. Students have the flexibility to engage in an art form that they are comfortable with for this assignment, providing you with an idea which forms of art, peak their interest. Student work produced from this assignment ranged from TikTok videos, Snapchat stories, playlists, and drawings. Below are sample responses to the questions:

Figure 1.1

| What is your greatest strength? |

|

| What is a character flaw you have? |

|

| Who are you? How do you see yourself? |

|

| What are you excited for? |

|

| What are you anxious or fearful about? |

|

Returning to Freire’s humanization pedagogy, “…the purpose of humanizing education is not only to transfer meaningful academic knowledge but to also promote the overall well-being of all students…educators attend to students overall well-being when they connect with students on an emotional level by (a) providing reciprocal opportunities to share their lives, (b) demonstrating compassion for the dehumanizing experiences students of color encounter…” (Salazar 128). The five student responses recognize the emotional level students engage in, when sharing their lives–an important aspect of relationship building in the classroom. Providing students with the opportunity to emotionally express themselves, through writing and art, creates an atmosphere of empathy in the classroom. Demonstrating compassion amongst student responses, writing back to them, answering their questions, and taking the time to analyze their responses contributes to the initial steps of decolonization–recognizing their individual identities.

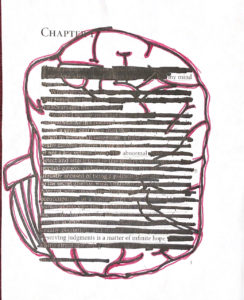

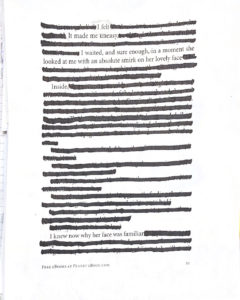

Pivoting off of this activity, includes the providing students the opportunity of working with the text, and art. This assignment is designed to build off of student made art, while cultivating poetry through a limited extent. Erasure poetry, also known as blackout poetry, is a form of poetry where a poet takes an existing text, and erases words to give the text new meaning. This activity builds off of the introductory arts and humanization prompt, as it allows students to work with an existing text that they may not engage or connect with. Each student was given a different page from the first two chapters of The Great Gatsby. With their unique page, students were tasked to create an erasure poem that conveyed a theme, from ones they identified as a mini-activity. This activity allowed students to visualize the creation of a work of art, both visual and poem, with a text they felt disconnected with. Below are student responses to the activity:

Erasure poetry further strengthens humanization in the ELA classroom, as students are given the physical liberation of marking up and alternating a text. Being able to restructure a page and make it their own, allows students to have ownership, building a connection with the work. Furthermore, turning the page into a visual image/work of art strengthens student understanding of the text as a whole, as they utilize information based off of theme and characterization, to produce a work of their own. Figures 1.3 and 1.4 demonstrate visual art, with poetry content tied towards the characters of Nick and Daisy, while Figure 1.5 demonstrates the identified theme of “second chances” within love. All three poems recognize a student tie to the traditional text of F. Scott Fitzgerald, while encouraging the creation of the traditional.

The two prior assignments build up to a third assignment that emphasizes student identity in the classroom. As humanization pedagogy, according to Freire, “…encourages educators to listen to their students and build on their knowledge and experiences in order to engage in contextualized, dynamic, and personalized educational approaches that further the goals of humanization and social transformation” (Salazar 127). The third activity proposed to encourage humanization, intertwined with arts and writing is heavily influenced by student identity, specifically language. Students are taught about the usage of description within The Great Gatsby. After recognizing the role of description in the text, students are posed with the following question: Are the best descriptions conveyed in English? As students picked apart the question, of the four sections surveyed, a majority of students responded with “no.” The pivotal statement that moves the conversation, is when a student says “Somethings in my language, cannot be translated to English.” Students must come to this recognition, and it is important as educators to note student ownership of language. Students tie language to their identity, and often take ownership and connection with their first spoken language, if it is not English.

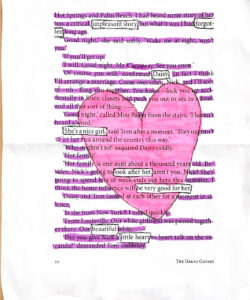

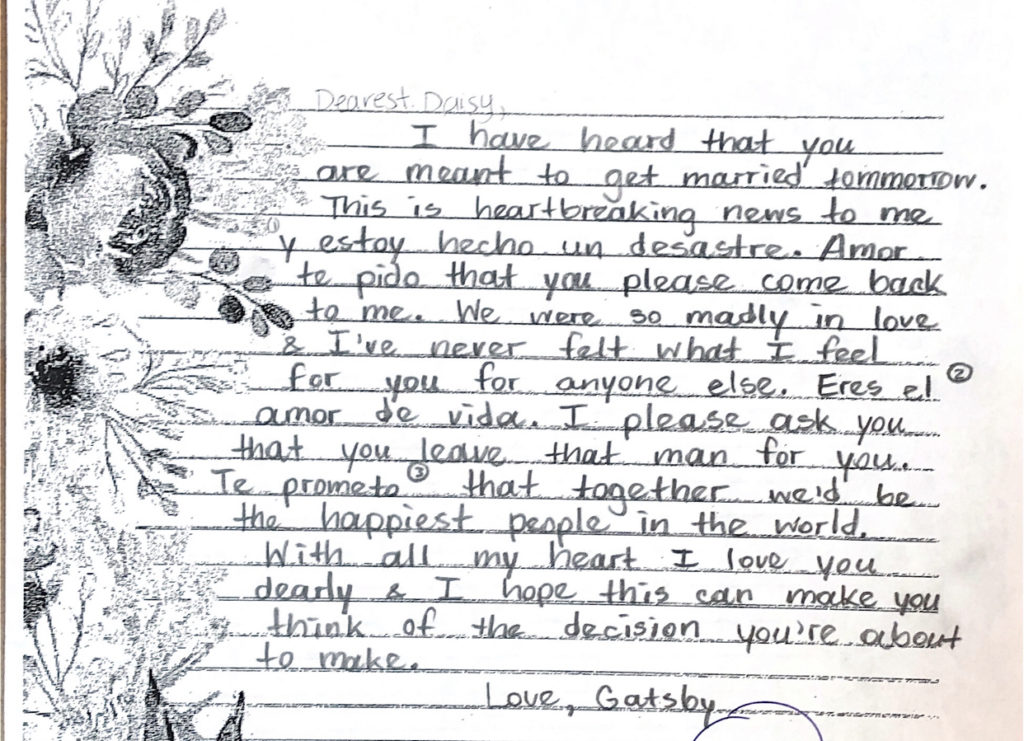

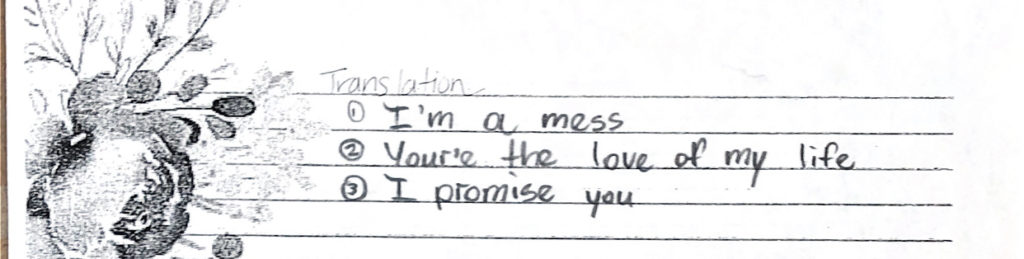

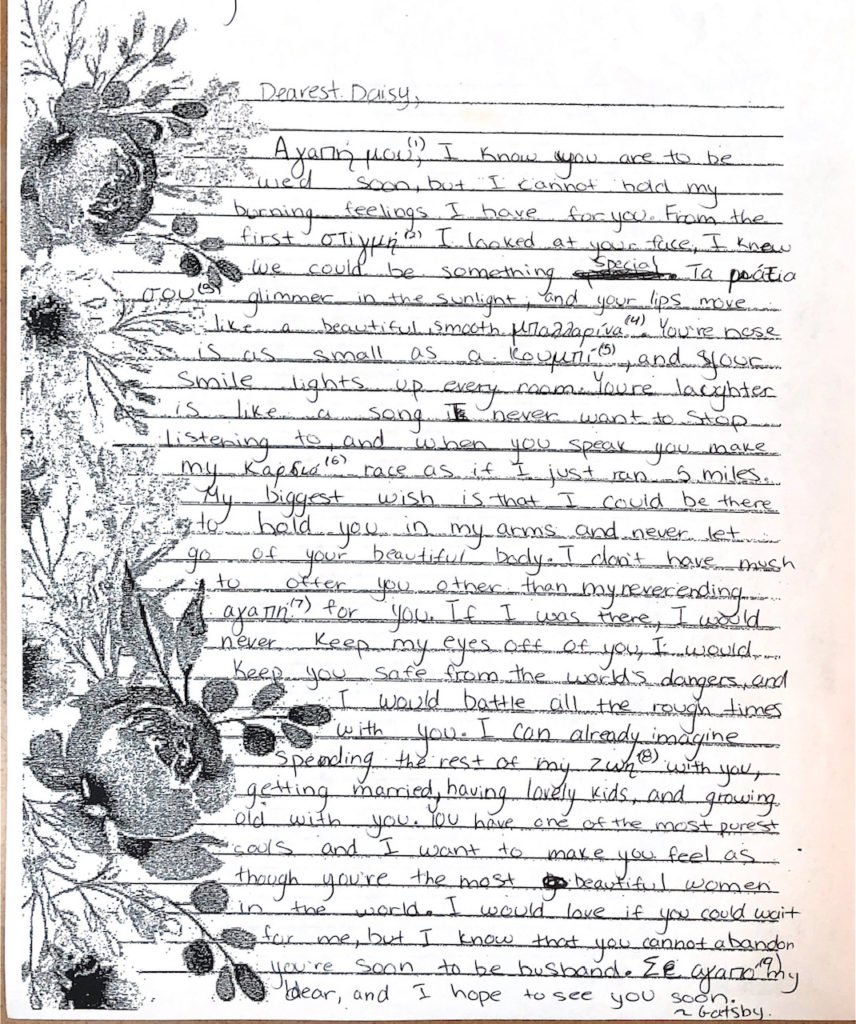

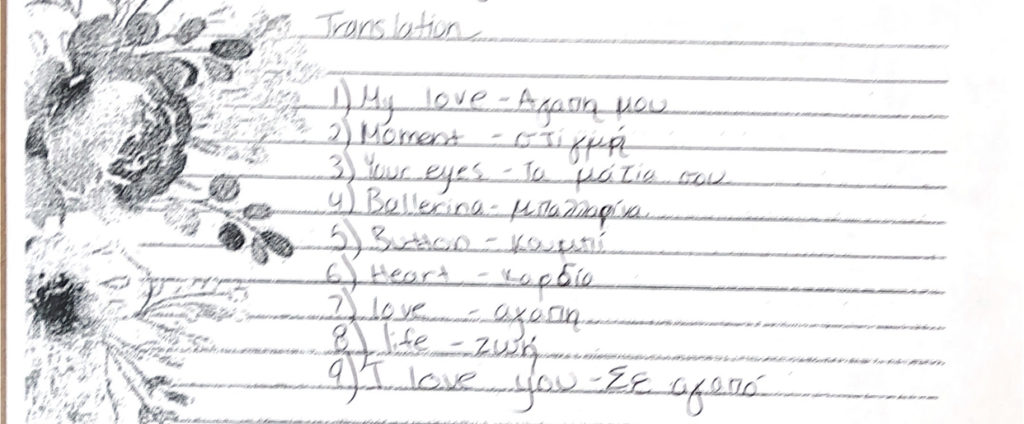

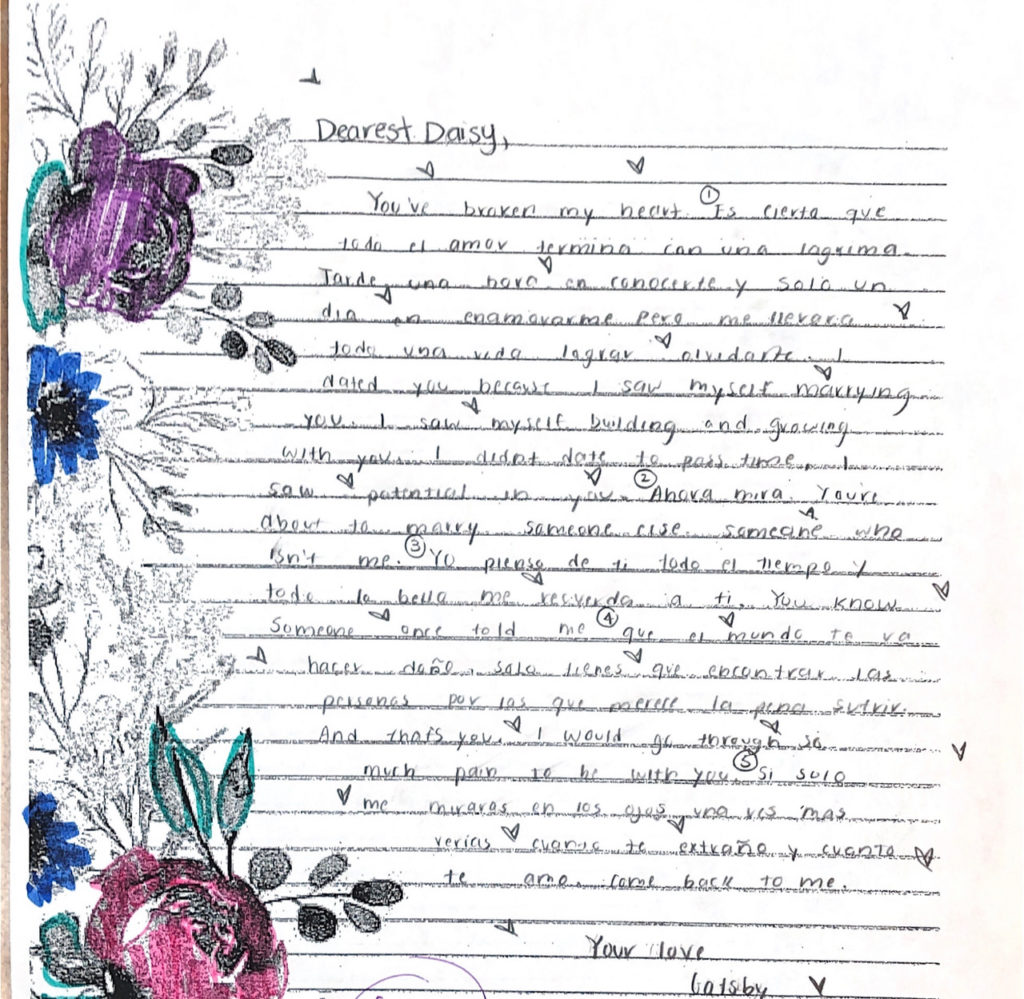

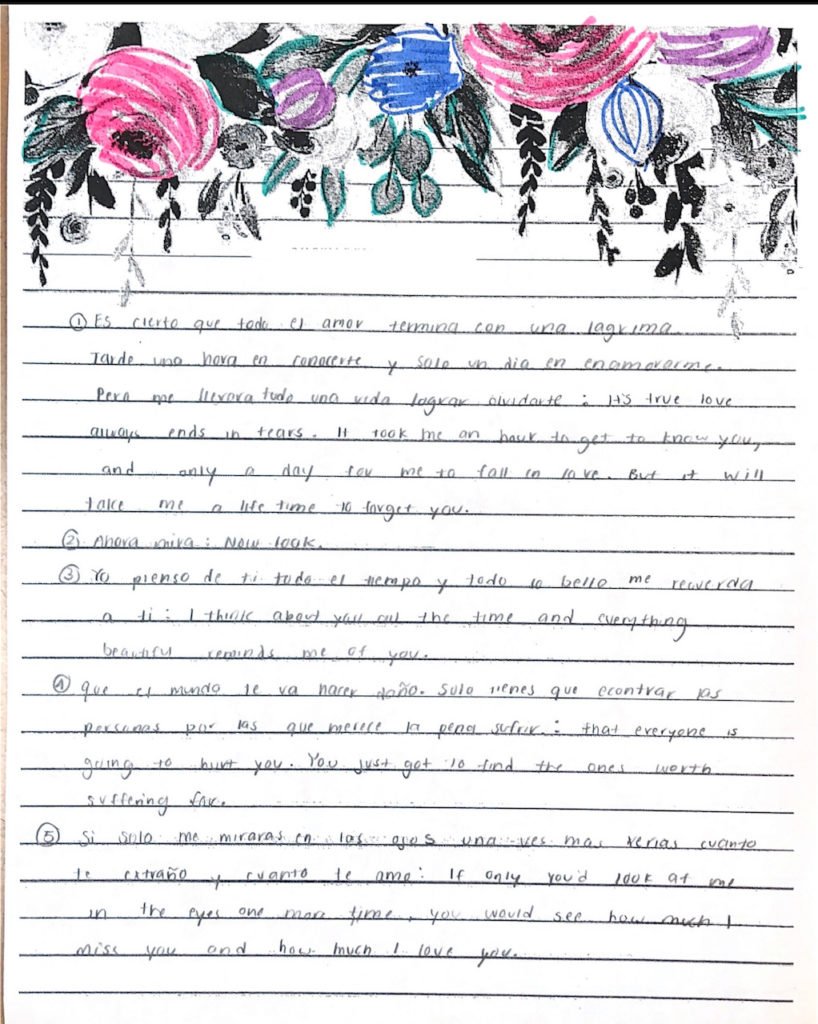

The concept of “code switching,” the practice of moving back and forth between two languages or dialects in conversation is introduced to students, along with the rhetorical appeals.. Students were then tasked to write a letter utilizing a rhetorical appeal, while engaging in descriptive writing that code switches amongst their native language. The letter, being the one Daisy receives on the day of her wedding, from Gatsby, that makes her initially call off her marriage to Tom Buchanan. It is important to recognize how to engage students who only speak one language, in this activity. Introducing the love letters of Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald helps model the idea of letter writing to students, as the selected letter focused on Zelda persuading Scott to come and marry her already. Students analyzed the letter, along with the dialect of English spoken both in that time period, and as a result of location. From this, students who only spoke one language, utilized various dialects of English, while all students benefited from a model love letter. Below are student responses to the activity:

The student samples demonstrated above recognize the levels of identity students engaged with amongst each letter. Figures 1.6 and 1.7 feature code-switching descriptions with a student whose first language is Spanish, while Figures 1.10, and 1.11 are written by a student whose first language is English. Figures 1.8 and 1.9 feature descriptions with a student whose first language is Greek. Student engagement exceeded expectations within this assignment, as many students seized the opportunity to incorporate their language and multiple dialect efficiency within their writing. Ultimately engaging and creating a piece of writing that humanizes their connection to the text, while bringing awareness to their identity outside of the classroom.

COVID19, Humanization, Writing, & Self-Reflective Educator Support

After attendance plummeted on Friday, March 13, I spent my weekend on edge, with fear of the inevitable. My papers were graded, the lessons were ready, the soccer and basketball signs were painted and packed. Over two hours, I picked up pennies, tiny stars, paper clips, marbles, and rubber bands, creating my signature “bags of happiness” for the goodbye approaching. While I consider myself intelligent enough to understand reality, when Mayor De Blasio announced that schools were closed, the young, child-like nature of my being came into play; this is unjust to me, was all I could think. I didn’t feel like Ms. Inderjeit anymore, and I no longer felt like I could be brave, I felt robbed. Through the days of comprehension and working through my initial emotions, I came to an understanding of humanization, and our work as teachers. While my students are our strength during times of uncertainty, we are an even greater pillar to the stability they need in times of trauma and fear.

As such, art and writing become crucial aspects of humanization during times of trauma, as they hold the potential for students to express difficult emotions, reparation through fear, and engage with writing, to cope with trauma. Crystal L. Park and Carol Joyce Blumberg analyze the relation between writing and trauma within their article “Disclosing Trauma Through Writing: Testing the Meaning-Making Hypothesis.” Park and Blumberg establish that overall research “…indicates that asking people to write on consecutive days about a previously experienced traumatic event, and in particular, to express event-related emotion, is associated with better subsequent health as indicators, including immune functioning, use of health services, and self-reported health (for reviews, see Pennebaker, 1993; 1997; Smyth, 1998).” (Park and Blumberg 597-598). Addressing this form of writing through our current circumstances, require teachers to play an advanced role within student work production. With the current COVID-19 crisis, ELA teacher concerns include students lacking resources, being disengaged, and simply refusing to participate due to resistance of remote learning. There is no “magic” solution to get students engaged, as the circumstances of 170 students are no longer controlled within our classrooms, but rather, in 170 home and living situations. To encourage humanization through writing, during a crisis such as COVID-19, teachers should base their efforts in a routine. Routines provide structure to our students and ourselves. During times of crisis, structure is disrupted, with the potential to leave ever-lasting effects. A basic routine to keep students writing over consecutive days while living through trauma can include, check-in questions to see how students are doing, Google Forms that prompt both routine and non-routine questions, or daily free writes/journal prompts.

Though free writes and journal prompts, students are provided with the ability to explore personal thoughts and emotions, with routine and guidance embedded in each task; designed to have students recognize and address the trauma they are experiencing. Park and Blumberg recognize the process of writing to cope with trauma through a secondary study, stating, “Pennebaker proposes that asking people to write about traumatic experience may work in two different ways, (1) by decreasing inhibition (i.e., lessening the cumulative stress on the body that is produced by nondisclosing) and (2) by facilitating assimilation or the making of meaning regarding the trauma (i.e., integrating the traumatic experiences into already existing meaning structures; e.g., Pennebaker, 1997; Pennebaker, Colder, & Sharp, 1990).” (Park and Blumberg 598). Bringing this sentiment forward during a crisis requires educator implementation of routine and patience. Having students consistently recognize they are in a time of trauma decreases the “shock” of our circumstances, and emphasizes the new, unpleasant reality. After students hold the ability to accept that this is our new norm, they are able to give each their familiar structures, new meaning. These new meanings include recognizing adjusted societal expectations, such as social distancing and wearing masks, comprehending school is still present within remote learning, and adapting to changes they were reluctant towards.

Maintaining stability as an educator during times of crisis is significant during this era, however it is not a mindset I have fully mastered. Times of trauma require us to be a pedestal for our students, however this does not imply that our trauma be relayed towards those around us, or ignored. As students miss their lives, educators miss theirs, as well. Educators recognizing the situation and changes during times of trauma is necessary to further the sentiment of humanization amongst classwork, even if it is remote. The relationships and interactions cultivated in your classroom have not gone away, students remember who you are and your time together. To continue to support your students, requires energy from a level unbeknownst to educators each day. Educators must remember to take a step back and engage in activities that allow them to make meaning of trauma. Suggested activities that cope with the loss of the physical classroom, include bullet-journals with writing tasks. Below are several writing prompts, encouraging teachers to recognize and make meaning during times of trauma:

- List 10 classroom moments you never want to forget

- List 8 moments that made you proud to be a teacher

- My student said…on this day…and it changed me because…

- Moments where I know my students appreciated me

- Moments where my students knew I appreciated them

- If I could go back, I would change…

- To my students, during times of trauma, I would like you to know…

These prompts force teachers to address the trauma they may ignore during times of trauma. While difficult to answer, in recognizing our emotions and the disruption of our lives, we are able to make sense of our trauma, to mentally support ourselves. An educator cannot come to the aid of their students, if they do not address their emotions, and hearten themselves first.

Conclusion

Returning to Freire’s humanization pedagogy, and those that implement his theory in the classroom, the five key tenets, to successfully create such an atmosphere in the classroom include:

1. The full development of the person is essential for humanization.

2. To deny someone else’s humanization is also to deny one’s own.

3. The journey for humanization is an individual and collective endeavor toward critical consciousness.

4. Critical reflection and action can transform structures that impede our own and others’ humanness, thus facilitating liberation for all.

5. Educators are responsible for promoting a more fully human world through their pedagogical principles and practices. (Salazar 128).

Educators are creators. As creators, our work to help students recognize their identity, and play a role in the “full development” of the adults they are becoming, is continuous. As teachers, we are responsible for elevating our students, to become educated, aware, and engaged members of civilization. This responsibility, and our ability to humanize our classroom, liberates efforts to transform the structures of colonization within our educational systems. The influence of colonization will take years to undo, however our efforts in impeding these structures contributes to the progress needed for ultimate decolonization. Above this, the “journey for humanization” and the passion to bring such forth in classrooms, is up to you, as the teacher. Freire says “To deny someone else’s humanization is also to deny one’s own,” denying students the ability to engage with their identities during a crucial time of their development, is to deny them as our students. The journey our students take to become “full human beings” requires room for trial and error, consciousness that engages their identities, morals, and opinions, that cultivate critical thinkers. Humanization in the ELA classroom is complicated, and the road is burdened with mistakes, errors, and failures. However, it is our role to recognize and make these mistakes, to elevate our students. Above all efforts to humanize your classroom and become a better educator, within the passion, creativity, and love you bring to the profession; above all else, as said by Vincent Van Gough, “All that is done in love, is done well.”

Works Cited

del Carmen Salazar, María. “A Humanizing Pedagogy: Reinventing the Principles and Practice of Education as a Journey Toward Liberation.” Review of Research in Education, vol. 37, no. 1, Mar. 2013, pp. 121–148, doi:10.3102/0091732X12464032.

Park, Crystal & Blumberg, Carol. (2002). Disclosing Trauma Through Writing: Testing the Meaning-Making Hypothesis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 26. 597-616. 10.1023/A:1020353109229.

Sanchez, Nikki. “Decolonization is for Everyone.” YouTube, uploaded by TEDxTalks, 12 March 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QP9x1NnCWNY.

Tuck, Eve & Yang, K.. (2012). Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor. Decolonization. 1.

Multimodal Brainstorming with Word Clouds

by Gregory Iciano

Remote learning has definitely gotten me thinking about multi-modal forms of engaging students. Especially, since I teach a lot of ELLS. And in my pursuit of enhancing my engagement I’ve come across some pretty cool ideas. Over the past few weeks, I’ve been exposed to countless applications, websites and activities during remote learning. One of the websites that stood out to me was a website called https://wordart.com/create. I decided that I wanted to have my students create a word cloud, in part because I wanted to engage them using something other than writing. A word cloud is literally a cloud of words put together in a specific layout and the layout of that cloud is totally up to the person creating the word cloud. The unit that we are working on is a unit on identity. So, I decided that the word cloud should obviously be about my students.

So, before I go into any further detail about the assignment or even the unit it would help to explain the class that I’m teaching and the student population. The class is a composition course and it’s a mixed class with 9th and 10th graders. It’s a general education class with about 4-6 ELLS and a total of about 20-25 students. The ELLs range from entering to commanding and there are two students who are entering ELLs that do not understand English. As for the unit it’s a unit on Identity and the resources that I had gathered were mainly from New Visions. Originally, the plan was to have students possibly draw a self-portrait of themselves. However, I didn’t think most of my students would’ve liked that and it might’ve been cumbersome for my students to post images of their drawings. So, I decided that towards the end of the first week of the unit that they would be working to create a word-cloud about themselves. So, this is how I stumbled upon word clouds because they’re a good substitute for a self-portrait. In some ways they are self-portraits. So there were three elements that I had in mind when I actually was searching up websites that allowed you to create word clouds aka word cloud generators. I was looking for a website that was user friendly, easy to navigate and the most important of all, free. The only issue with this assignment now that I look back at it in hindsight is accessibility to technology. Because of course if they can’t access this website they can’t engage in the assignment.

However, I had a couple assignments that led up to the word cloud. There was a graphic organizer that asked students several questions about their identity and I also assigned a discussion question pertaining to identity and had students respond to each other’s posts. The day before I assigned the word cloud assignment, I had a Do now question that asked students to write 5 adjectives that described them (extra credit if they used these adjectives in sentences) and I also hosted a Google meets session with my students and walked them through the website and it’s features. The day of the assignment I asked them to write another 5 adjectives and to use them in a sentence. Essentially I had asked students to include a minimum of 10 adjectives or sentences that would describe them. I gave my students a model example of a list of adjectives that I came up with and a model of a word cloud based off my list of adjectives.

The image posted above is the layout of the word cloud generator and it’s the only page you’ll ever really need to be on when you’re on this website. The word cloud is created by inputting/typing the words on the top left side. You can adjust the actual shape of the word cloud.

The fonts of the words in the word cloud could also be adjusted.

The layout of the cloud could also be adjusted, which just means that the layout of the words in the cloud can be changed.

Then there’s also a feature to change the style of the word cloud. But one of the most important things to note is that after you make all those changes on the left side that you press the red “visualize” button on the right side. By doing this you’ll actually get to see the changes you made on the left hand side.

Lastly, I wanted to include some of the word clouds that my students created. So I’m going to include 3 word clouds created by my students: