This chapter contains two sections:

Using Writing to Heal

Writing to Promote Student Wellness and Interactions

Using Writing to Heal

by Allison Bigelow

If he wrote it he could get rid of it. He had gotten rid of many things by writing them.

–Ernest Hemingway

People have used writing to express their feelings, work through life’s twists and turns, and to evaluate one’s own complex idiosyncrasies since written language has been widely used. Given that psychotherapists are still in business, it stands to reason that this is not always an innate ability. As English teachers in a standards-heavy world, you have probably been discouraged from leaning too heavily on expressive writing due to its “lack” of rigor. This is a flawed view.

Self-expressive writing is healing. Working through our traumatic experiences and our own often overwhelming emotions through words can be cathartic and lead to real epiphanies about our own motivations or path forward. Writing for healing seems like a perfect fit for small groups with a social worker or with one’s art therapist, but it belongs just as naturally to the classroom. Encouraging students to engage in self-expressive, healing writing on a regular basis will lead to increased trust in your classroom community, improved learning outcomes, and stronger writing skills.

What is trauma?

Trauma is an extremely distressing event or injury. Trauma can be physical, psychological, or both. For example, someone who falls from a window and breaks a bone has been physically traumatized, the bone, muscle, skin, and other tissue has been damaged. Someone who has, like Harry Potter in the cupboard under the stairs, been confined in small spaces for long periods of time may become psychologically traumatized as a result of their confinement. Someone who has experienced something like a car accident with fatalities has experienced both physical and psychological trauma.

Every single person on the planet experiences some trauma in their lives. It is what prompts our brains to recognize and adapt to threats in our environments; it’s inevitable. In fact, most of us experience our first traumas in early childhood, and, as teachers, we should be mindful of trauma and its impact on our students. Some of these traumas may seem insignificant to our adult minds, but think back to a time when you were in first grade and someone bullied you or made you feel embarrassed in front of the entire class. How did you feel when that happened? It probably felt like a wound that would never heal–something you and your reputation could never hope to survive. That’s trauma, and when compared to neglect, abuse, poverty, illness, and death that children all over the world experience every single day, small potatoes. With this in mind, it’s important to not allow our adult hierarchy of severity regarding these traumas to affect the way we interact with students who have experienced either (so, all students).

Trauma causes stress, regardless of whether or not the event in question rises to a level worthy of such a response. Stressed brains can’t learn. Stress causes dysfunction in concentration, focus, memory, social interactions, mood and emotional regulation, among many other unsavory effects. If a student broke their leg in the middle of your lesson, you wouldn’t expect them to keep up with parts of speech or Romeo & Juliet. We understand intuitively that intense physical pain impedes our cognitive ability, but the same principles apply to psychological trauma just as much.

While we are not therapists and the psychological healing of our students is not our “job,” it is our job to ensure that our students are learning and feel supported in our classroom. We cannot do that successfully by ignoring our students’ physical and mental condition and pretending like everything is okay all the time. In times of global crisis, like this pandemic, nothing is okay, and students need even more of our support than ever. Healing writing is one content-aligned mechanism to do so.

How can writing help?

In order to heal from trauma and become a productive member of a classroom, students must develop resilience, the ability to achieve positive outcomes despite adversities. These outcomes and adversities can be physical, mental, emotional, social, or spiritual. Building resilience is inextricably linked to the education system, one of the few places children have opportunities to strengthen this skill. The development of resilience in children relies on four factors: self-efficacy beliefs, emotional and behavioral self-regulation, strong relationships with mentor adults, and hope. As English teachers, we have a role to play in all four of these. It’s no coincidence that English teachers are stereotypically the ones that students are closest to emotionally and trust most.

Much of middle and high school literature curriculum focuses on coming-of-age narratives which impart hope and relatability to students’ lived experiences. There are several popular titles in the modern “canon” of secondary ELA curricula such as The Outsiders, The Hate U Give, The Fault in Our Stars, and Speak that deal with trauma responses and coping skills in response to intense and distressing experiences. This is really useful for students as models for self-regulation as mentor texts and characters as mentor personalities of sorts. Assigning or recommending these types of texts to traumatized students can also have the effect of strengthening the bonds of trust between you, a trustworthy adult, and that child. However, it is not enough to support our students in this sort of passive way.

Fictionalized accounts of trauma, while helpful, are still fictionalized. They reflect the writer’s perspective of a stable narrative of the traumatic event. Stable narratives are a very important part of integrating and healing from trauma; our brains are a lot like complex, biological computers. We don’t handle uncertainty or paradoxes very well. We are most comfortable when things make sense. By its very definition, trauma is nonsensical. Many times, traumatic incidents destroy preexisting understandings of the the way the world works, causing disequilibrium and confusion.

In some ways, it is a natural adult instinct to want to rationalize an experience for a traumatized child. Our prefrontal cortices are far more developed than a young adolescent’s, and we may believe that we understand what’s happened to them better than they do. We don’t. Children are experts in themselves. They experienced the trauma. The relationships they have to others involved in the situation and their individual worldview are not available to us, and as such we cannot tell that story for them in an authentic way. Students should be given the space to express their stories in their own way without our input.

Writing about a traumatic event allows children to integrate the experience into their existing schema and worldview. They can construct a stable narrative, one in which the unprocessed contradictions are exposed and worked through. Writing about these events will also help students to identify, explain, and interrogate the complicated and multiple emotions stirred by such events. The culmination of this writing-processing is understanding why an event occurred and what, if any, responsibility they bear.

The notion of using self-expressive writing to heal psychological wounds may sound a little “woo woo” on its first face. It may elicit images of hippies and others prone to touchy-feely pseudo-science, but healing writing could not be further from this. Dr. James Pennebaker is the foremost researcher in the field of healing writing and has been studying the effect of self-expression on physical and psychological healing since the 1980s. From the initial trials, it was clear that writing for healing was an effective intervention. While psychological outcomes can be more difficult to prove, Dr. Pennebaker also discovered that this type of writing was just as effective in supporting the healing of physical injuries as well.

In one study, Dr. Pennebaker tested the effectiveness of expressive writing in adults with wounds. The experimental group was asked to write expressively for twenty minutes per day for three consecutive days. A control group was asked to write an objective recounting of their daily activities for twenty minutes per day for three consecutive days. Two weeks later, each participant was given a biopsy to measure the rate of healing of their injuries. Those who participated in expressive writing experienced twice the rate of healing from the control group. Pennebaker also discovered that when comparing expressive writing and thought suppression regarding traumatic incidents, immune function of those who participated in expressive writing was measurably stronger than in those who did not. Asking students to face their challenges instead of hiding from them can really support chronically absent students and to increase overall outcomes.

When to use healing writing

Giving students opportunities to regularly engage in self-expressive activities is extremely important. Not all expressive writing is built equally, however. Expressive writing is not simply diary writing or cataloguing the events of the day–or even of the traumatic event–in an objective sense. Expressive writing is not rumination or engaging in self-victimization or self-blame.

The two essential functions of expressive writing are catharsis and insight. Getting your emotions out of your body and into the air or onto the page sometimes feels like taking a weight off of your shoulder. Catharsis floods our brains with dopamine and endorphins. We feel great for finally telling our story. Expressive writing cannot stop there, though, or it’s just self-indulgent. Insight is just as necessary an element to the healing nature of self-expression. We must teach students to write their stories, but to learn from them, too. Sometimes those insights are minor, we make small realizations about our own motivation, for example, but others can be major and to help integrate trauma into one’s psyche.

Using healing writing is most useful when dealing with trauma that is in the past (perhaps in childhood), dealing with current trauma (a house fire or car accident, say), a big change (moving, going to middle/high school, graduation) or to still anxiety (like, say, about a pandemic).

When might writing not be useful?

There are certain moments in which using healing writing to support a student through trauma is more harmful than helpful. Writing to heal trauma can really only be useful when the writer is ready to face the incident. For example, if a student has recently lost a parent but has not come to terms with that loss or is not ready to talk about that loss, asking them to write about the funeral will cause more harm than good. Everyone heals in their own time, and attempting to rush that process is definitely not in our purview as educators.

Writing to heal works best when the trauma in question is a particular event or series of events. When it comes to grief, particularly the death of loved ones, writing about that pain does not speed up the healing process, but it doesn’t hurt it either.

Teachers should exercise caution when it comes to students writing about ongoing trauma. Human brains are far more prone to anxiety and catastrophizing than to predicting future outcomes rationally. Adolescent brains are even worse at this. Students that are in the thick of ongoing trauma should be discouraged from attempting to predict the future. For example, say a student learns that they or a close relative have been diagnosed with cancer. The student or loved one may not be as strong as they had been before the diagnosis, but they are continuing treatment. The prognosis is unclear. Students writing about this type of experience could be dangerous. If a student predicts that they or their loved one may die, writing about this death can cause increased stress, fear, and anxiety.

Teacher FAQ

To riff off of the USS Enterprise’s Dr. McCoy, I’m a teacher, not a therapist! How and why is doing this work my job? Also, how am I supposed to justify this stuff to my administrators!?

In its most basic essence, your job is to ensure that students learn English Language Arts to the standards implemented by your state of employment. We discussed earlier that stressed brains cannot learn, and if a few minutes of self-expressive writing can be the difference between learning and retaining nothing, why wouldn’t you? Additionally, social-emotional learning (SEL) is a cross-curricular overlay in many schools. Self-awareness is a prerequisite for identity, social, and behavioral development. Self-expressive and healing-centered writing can be a powerful tool to develop it(through the use of prompts, for example).

What if writing about an experience for my class causes a student to commit suicide?

There is a significant body of evidence that suggests that the opposite is typically true. Students are at significantly higher risk for suicide and self-harm when traumatic feelings, events, and stories go untold, repressed, and unprocessed. Unless you for some reason demanded that that student write about something they weren’t ready to, your passively assigning self-expressive writing will not be enough to trigger something like that. In all likelihood, that student was considering harming him/herself long before they sat down to write an essay for your class.

How am I supposed to grade this kind of writing? Your trauma is only worth a B-?

Contrary to what you might think, students writing expressively actually make fewer grammatical and spelling errors than when writing about anything else. It is obviously unethical to attempt to grade on content or to dismiss or invalidate experiences. It is common practice to grade such types of writing on completion and save formal formative assessments for different writing assignments.

How is this not just an extension of participation trophy culture?

If you really, truly believe that dealing with trauma and supporting students’ learning as well as their social-emotional development is this trivial or time wasting, please find a new profession.

What if teachers use this type of writing to prey on their students?

I think this should go without saying, but if you witness a colleague do this, report them to administration and to the child abuse hotline.

What if a student admits to committing a crime in an essay?

Most students will not spontaneously disclose crimes to you, especially if you don’t have a trusting relationship. However, if this is something that concerns you, create and reinforce a disclaimer that you are a mandated reporter.

What standards does this type of writing fulfill?

As I mentioned above, it ties in really well with social emotional learning. Not everything has to be assessable by a standard to be valuable.

What do I do if I feel traumatized by these responses?

Vicarious trauma is a real thing. We are often traumatized by the stories of others, particularly children. Commit to practicing self care. Don’t read every response closely if it’s not necessary. Take time for your own mental wellbeing by seeing a therapist, practicing mindfulness, expressing gratitude and love, or perhaps try some healing writing for yourself.

Suggestions for future use

- Heart Maps – This idea, that I discovered from this website, is a pre-writing strategy that can be used to great effect in the genres of memoir, personal narrative essay, fiction, and poetry. It requires very minimal preparation, too, which is probably the best part. All it requires is a blank sheet of paper with a big ole’ heart in the middle. The symbolism is helpful for students to brainstorm any emotion, positive or negative, so the usefulness extends even beyond using it for healing writing. But if you are interested in using it healing writing, you’d ask students to fill their hearts with all of the things making them feel sad, anxious, angry, frustrated, etc. As stated above, healing writing can be helpful both for current stressors and childhood traumas. Students can then use these maps of their pain to visualize their emotions in a different way; sometimes this visualization sparks genius. Students can write in the genre of choice while constructing that more stable narrative of their trauma or stress.

- Free writing – Another easy strategy for facilitating this kind of writing to heal is to provide students many opportunities for unstructured writing time. You can choose to assign writing prompts or not, and these prompts can take many forms, including detailed prompts, single words or emotions, themes, or photographs.

Works Cited

- Hart, Kathryn, director. Trauma Informed Resilient Schools Professional Development Training. Starr Commonwealth, 2019.

- Moore, Beth. “Remember the Power of Writing to Heal.” TWO WRITING TEACHERS, 11 Nov. 2016, twowritingteachers.org/2016/11/11/remember-the-power-of-writing-to-heal/.

- Murray, Bridget. “Writing to Heal.” Monitor on Psychology, American Psychological Association, www.apa.org/monitor/jun02/writing.

- O’Connor, Meg. “Evidence of the Healing Power of Expressive Writing.” The UnLonely Project, 23 July 2017, artandhealing.org/evidence-of-the-healing-power-of-expressive-writing/.

- Pennebaker, James W., and Joshua M. Smyth. Opening up by Writing It down: How Expressive Writing Improves Health and Eases Emotional Pain. The Guilford Press, 2016.

- Purevsuren, Amy. “Writing to Heal.” Edutopia, George Lucas Educational Foundation, 30 July 2018, www.edutopia.org/article/writing-heal.

- Tyler, Lisa. “Narratives of Pain: Trauma and the Healing Power of Writing.” Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives in Learning, vol. 5, 2000, pp. 14–24., doi:https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1067&context=jaepl

Writing to Promote Student Wellness and Interactions

By: Nilaab Daftani

Through years within the American education system, the students aren’t simply developing analysis and deeper thinking skills, they are developing and fostering social emotional skill through interactions with their peers and friends. With the implementation of virtual learning in times of crisis, it is essential that students are still able to foster the familiarity and routines they had once had within the constraints of the online community. Through the use of specific resources and activities that look to help students further examine their own mental state and establish a community remotely, teachers can better reach out to students and provide activities/ learning that can help students feel within a community, even from their home or wherever they may be.

Introduction: Social Emotional Learning

Within the classroom, it is easy to let this aspect of student interaction fall through the cracks as teachers are more focused on assisting students in reaching benchmarks and standards in order to advance. Looking at the social emotional aspect of students is more geared to students who are developing in adolescent cognitive development, mainly within the elementary and even middle school setting. However, in engaging with teens and more mature middle school students it is important that teens and young adults feel competent, valued and exercise autonomy in their community, especially in the classroom. Students should have a sense of respect, and if they are engaged with instead of commanded, it may make them more likely to be more motivated and remain engaged within the classroom and community established.

In times of crisis, such as during the quarantine caused by Covid-19, it is all the more important that students are engaged, establish that autonomy and build bridges to reassure students that they are recognized as beings that go beyond grades and labels of compliant or noncompliant. In order to combine the social emotional aspect into the Language Arts class, students can engage in a variety of writing activities that look to align to standards but address difficulties in internal struggles that they may be facing. Other options is to possibly conduct a cross curricular project in which students are focusing on health aspects of humanity; physical, emotional, intellectual, social, spiritual, environmental, and occupational and conduct a research project closely examining each aspect of health and infusing poetry or sections of literature that can reflect their research. This can be offered as group project in order to promote student interactions, especially if the crisis is forcing students to quarantine and miss on that important bonding experience with their peers.

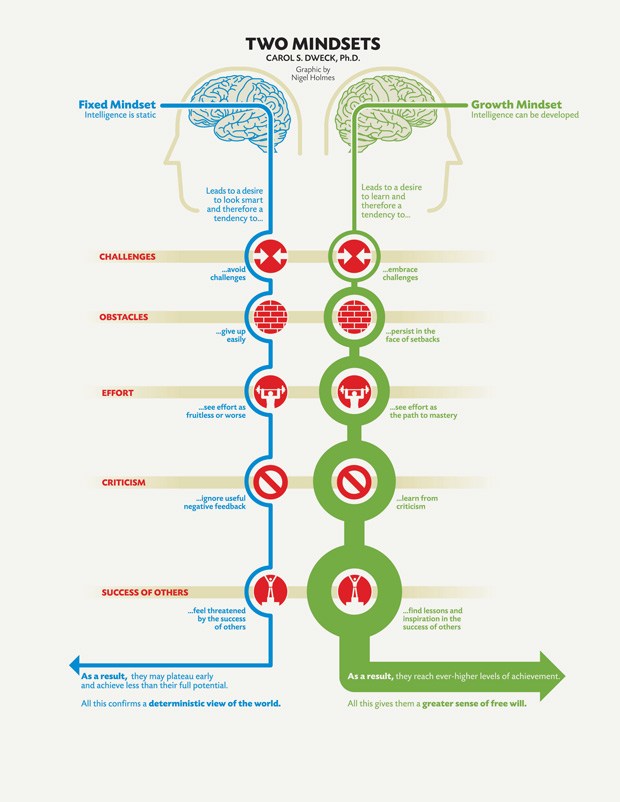

Growth Mindset vs Fixed Mindset

Engaging students in a lesson on the differences between a growth and fixed mindset is a great introduction into more self reflective writing and activities. Reflecting the different ideologies of Piaget and Vygotsky, a fixed vs growth mindset looks at students’ talents and abilities and the fluidity of both. Are talents and student abilities/ capabilities fixed or is there growth through hard work and self reflection? Engaging students in activities that force them to look at their own experiences, biases, situations where they did not think beyond their own abilities and constraints is a great end of year response, especially for the online remote experience as students are forced to reflect on their downfalls and areas for improvement, while looking at academic work they have completed.

The Reflective Essay

This can be more structured, i.e. the essay format, or it can be modified and implemented over a series of freewrites. Engaging students in an end of year reflective writing, or even an end of unit reflective essay can provide students with a structured opportunity to explore their pitfalls and accomplishments and offers students an area where they can express where they were not flexible and where they may have shown or demonstrated they have reached a goal. For my Freshman students, one of the assignments I am having them complete is a self reflective essay on their first year of high school, especially with the mass exodus to remote learning. Students were asked to reflect on their experiences, how they have grown from the middle school experiences, what they have gained in experiences and what they hope to learn in the future. This activity can also be reversed.

Another version that I had completed was asking my 11th grade students to write a letter to the Freshmen students, and in that essay they were asked to look back on their own experiences from freshman year and what wisdom they would impart on their peers. The results were interesting in that students wrote advice that they wish they could repeat to their younger selves, things like “Don’t get distracted by females” or “Going to class is all you need to do. Don’t get stuck repeating a grade. You don’t want to be here longer than you have to be.” and looking at how students were able to be more reflective and incorporate their own growth mindsets as an example for younger students works as interaction between students as well as offering students an opportunity to engage in the social emotional aspect of education that they do not frequently get a chance to do.

Poetry/Literary Analysis

Engaging in the growth mindset is great in theory, however in terms of implementing and keeping things standards and curriculum oriented, another great option is to include a lesson on the growth mindset into a poetry unit or do a mini unit. Two examples of poems that can be tied into a greater unit like S.E Hinton’s “The Outsiders could possibly be: If by Rudyard Kipling and Gold by Robert Frost. Both poem look at time and change and tie into the great self reflective piece through Ponyboy’s point of view and students can both analyze his greater reflections through the lens of the poems and then imitate the poetic language and procedures. It also opens the conversation to talk about trauma and loss of innocence, which can also easily mirror what students may be facing in crisis and through remote learning. Students can easily identify and contemplate how they have changed themselves.

Social Emotional Typewriter Project

The Poetry Society of New York created a social experiment that they labeled “The Typewriter Project,” that invited passersby to join a poetic exchange. The idea was to set up strategically placed booths that contained a vintage typewriter, one hundred feet of paper and a USB typewriter that allowed for all keystrokes to be recorded and uploaded online. The idea of inviting strangers to come and create collectively, pick up the voice that last left off and change/shape the conversation that people are having. The Poetry Society wrote on their home page that “Typewriter Project’s mission is to investigate, document, and preserve the poetic subconscious of the city while providing a fun and interactive means for the public to engage with the written word.” and it would be a fun remote experiment to investigate the subconscious of the student body even when not in the building collectively.

Students require a place or area in which to plot their thoughts and ideas, to vent to one another and in general, as they would with a teacher in person. Providing a class journal/ Quarantine Log that students can add their piece. Similar to The Typewriter Project by the Poetry Society of New York, students can add a line everyday, creating one line of consciousness. This is a less structured activity but creates a classroom collage that holds the voices of all the members of a community in an area that is easily accessible to all students within the class.

The activity would engage with social emotional wellness and offer opportunities for student engagement with one another as well as a safe space for creative collaboration.

This idea can also be modified and implemented as a ‘freewrite’, if students are apprehensive to share their work with a greater audience. Having students create and focus on streams of consciousness produce work that is inherently honest and raw, without the edits or forethoughts, although the process of freewrite/ stream of consciousness needs to be demonstrated and taught as students are not adjusted to having creative license and lack of forethought into their writing. However the teacher plans to implement this idea, it is about writing about a shared experience, giving students a topic and seeing what they can produce without the constraints of strict academic limitations.

This is showing the kids that their feelings are valid and have a place in the classroom.